Most digital marketing companies spend weeks of effort and thousands of pounds on paid search campaigns, generating SEO strategies, posting on social media and building landing pages to squeeze out a few percent more conversions.

All of these things are worthwhile, but often overlook a core problem that’s easy to fix and makes a drastic impact on revenue — your website’s loading speed!

Yoast, 2017

Every millisecond is an opportunity for users leave your site in frustration, and it happens more than you might expect. If your web pages take more than half a second to load, revenue is being lost. After crossing 3 seconds, 50% of your visitors may have already left before viewing the page!

Slow websites can be caused by everything from lazy developers to rogue plugins, content management systems, tight deadlines, lack of awareness and bad server configuration, and can severely hamstring the revenue potential of your website.

We’re often challenged by our clients to explain the value in spending extra time optimising for speed, so we’ve written this post as an in-depth guide laying out the problems facing bloated websites, why clients should care and how developers can set up their websites and servers for maximum effectiveness.

Reach out to us on Twitter if you have any questions or tips for us.

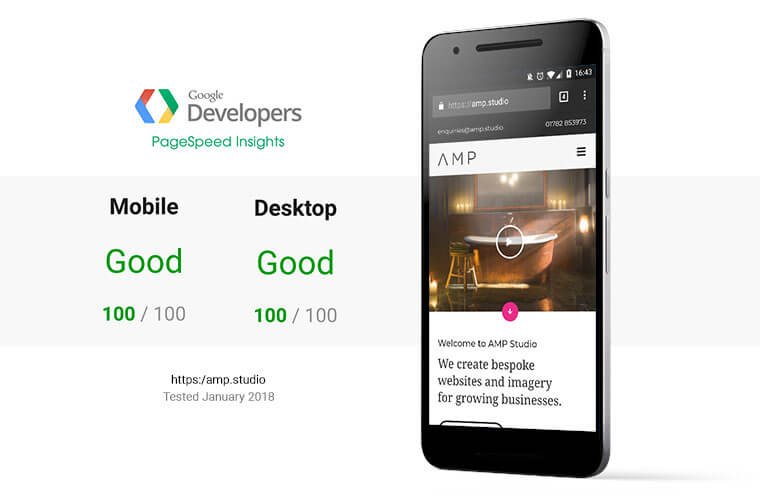

Setting high standards

We build our websites for ludicrous speed. As a baseline, we aim for 100/100 Google PageSpeed ranking and a load time of under 300 milliseconds (top 1% of all sites) in Google Chrome desktop over a good UK broadband connection. We also use Pingdom and GTmetrix for additional testing.

Call it overkill, but there’s a huge difference in conversions when a website is literally 10x faster than it’s competitors, and if you build for speed from the start it’s not too difficult to do.

Why benchmarks matter

Of course, benchmarks are not the measure of a good website, nor should they be a primary focus for the client. The design still has to be fit for purpose and easy to navigate.

Benchmarks expose any technical issues to present an objective, detailed breakdown of where your site could improve, thereby enforcing best practices for web developers.

We consider a PageSpeed score of at least 80 and a load time of under 1 second to be realistic and beneficial for any website. Top marks aren’t necessary, but there’s no excuse for not following most of the guidelines.

Developers — we recommend building at least one website against these metrics, even as a side project. Just understanding them can change the way you code in the future. We’re constantly shocked at how many websites fail to address basic rules like caching and compression that make a huge difference to loading speed!

So what?

Put simply, a faster, mobile-friendly website directly leads to more revenue, more conversions, better SEO ranking and more time spent on your site.

If you’re selling products or trying to convert leads, optimising your site’s loading speed should be your first priority. You can’t capture customers if they’re leaving in frustration!

Maile Ohye, Google Search Team

Watch Maile Ohye’s Site Performance For Webmasters for a chart-filled dive into how loading times affect e-commerce sales (spoiler: it matters a lot).

Direct revenue gains

Even before the mobile internet boom, the internet giants were testing relentlessly to make sure that their web pages performed optimally. Many of them have written about how faster pages substantially increase their metrics.

- Amazon gains 1% more sales for every 100ms decrease in loading time

- Google lost 20% of their traffic by adding 500ms to their loading time

- The BBC loses 10% of their visitors for every second of load time

- Trainline boosted sales by £8 million per year with a 300ms speed-up

- Yahoo suffered up to a 9% drop in traffic from a 400ms increase in loading time

- Facebook saw up to 25% more page views and higher engagement in casual users after speeding up their news feed

- AliExpress gained 10.5% more orders and a 27% increase in conversion rates for new customers after shaving 36% off their load times

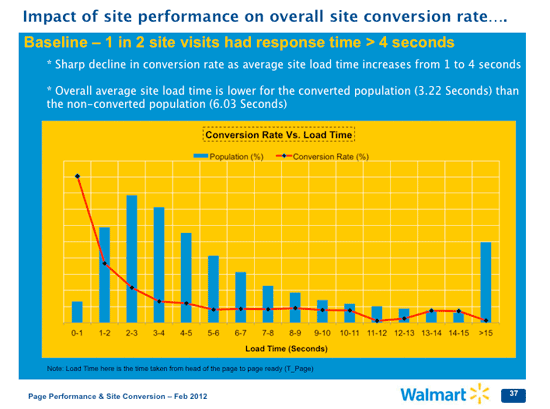

Conversion Rates

Walmart’s internal research shows a clear decline in conversions due to higher loading times. Note the huge drop-off from 1-2 seconds!

TagMan found that every second of delay can cause a huge 7% drop in sales. This can easily amount to thousands or millions of pounds lost every year for an e-commerce website, and sometimes a single line in a configuration file is all it takes to re-capture it.

SEO Ranking

As of July 2018 Google will penalise slow loading times on mobile in addition to desktop searches, and they already index for mobile-friendly layouts first in their search rankings.

Google, 2018

It makes sense — mobile devices took over 50% share of page views globally last year, and the impact of loading speed is more obvious on slow mobile networks. Users browse longer, view more pages and are more likely to return if a website is fast, all of which affects SEO. Google intend to start by only penalising the slowest websites, but the direction that they’re moving is obvious.

It’s quickly becoming table stakes to have a fast mobile-responsive website, and competitors who invest in the area will quickly gain an edge over slower sites.

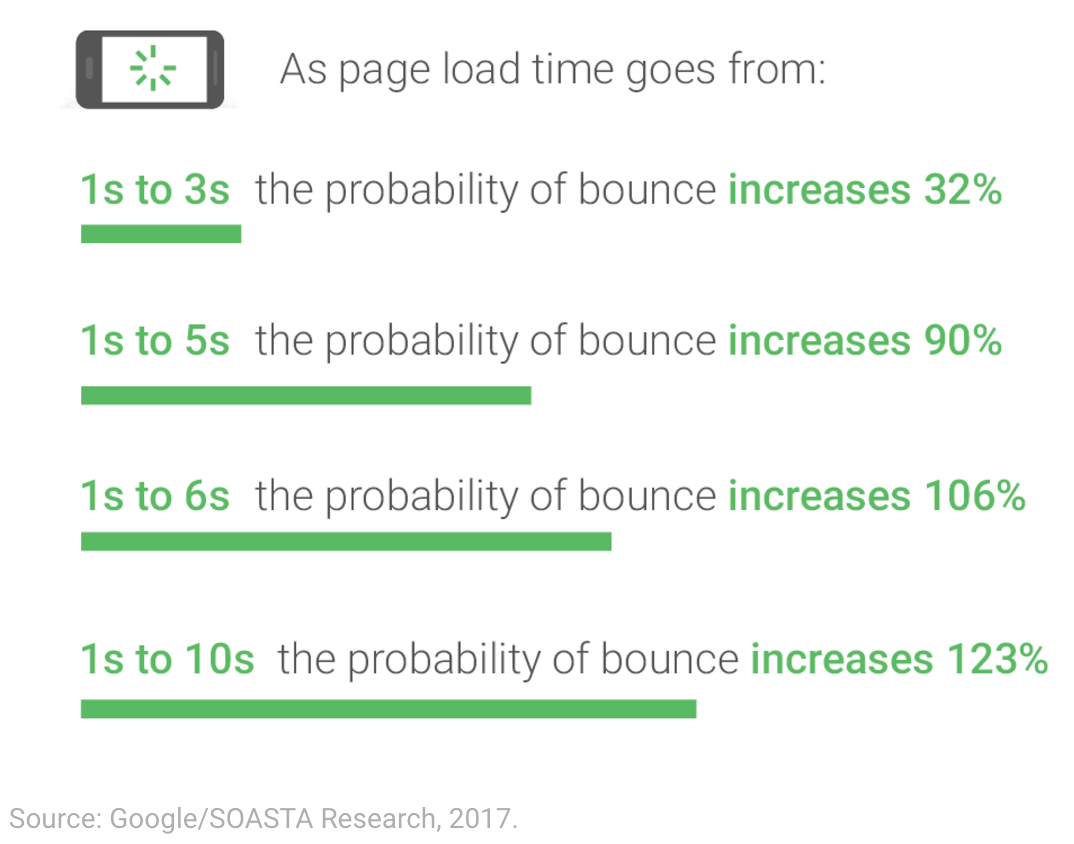

Lost visitors & bounce rates

According to DoubleClick by Google, more than 50% of visitors abandon a website during the first 3 seconds of loading, affecting your revenue and SEO rank. Given that the average mobile site takes over 19 seconds to load, there’s a good chance that your site is leaking visitors that could easily be recovered with a few tweaks.

Visitors are more likely to browse around your website, find what they’re looking for and stay for longer if your pages load quickly, leading to lower bounce rates and improving SEO rank.

Additionally, Google Analytics found that mobile websites that load in 5 seconds compared to 19 seconds gain:

- Up to 100% more ad revenue

- 25% higher ad viewability

- 70% longer average sessions

- 35% lower bounce rates

It’s clear from Google’s own research that any time shaved off a page’s loading speed makes a difference to the number of people who stick around, leading to more conversions, lower bounce rates and a higher SEO ranking.

iCrossing, 2012

Lower operating costs

A well-optimised website uses much less bandwidth and server resources than a bloated one, resulting in lower hosting charges and the ability to handle more traffic. This is great on busy e-commerce websites where hosting can cost hundreds or thousands of pounds per month.

No more crashing

Even a small web server can handle thousands of simple requests per second, but a bloated WordPress or Magento site can become overwhelmed under a small burst of visitors, even if it’s only 10 people clicking around at one time. That’s the last thing you need when your products get featured on a popular blog!

Why are websites so slow? 🐌

There are dozens of technical reasons for slow websites, but in our experience it comes down to tight deadlines, over-prescription of WordPress for cheap/quick projects (leading to the dreaded plugin/theme hell) or developers just being lazy.

Not testing on slow devices

Many developers are accustomed to testing their work over fast broadband connections on a high-end development computer, but neglect to test on an old Android phone over 3G internet.

We once audited a website for a popular restaurant that took 4 seconds to load on a 2017 MacBook using our office broadband, but 35 seconds over 3G. Why would your customers wait 35 seconds to find a phone number?!

Avoiding the problem

Slow loading is glossed over by clients and developers alike, because it’s a messy problem that’s easy to sweep under the rug, especially once the project is already underway. Few clients want to spend their budget on tweaking the loading times when there are features to be added!

Just like avoiding chores it’s a nagging problem that builds over time until facing it becomes a large upfront cost, but if controlled and built in from the start it’s easily manageable.

Lazy developers

It’s developer’s job to set up hosting correctly, keep on top of a site’s performance and ensure that modern standards are met. Unfortunately we come across websites every single day that are hamstrung by misconfigured servers, uncompressed images and bad coding.

These things can be fixed quickly and should have been set up in the first place, but are overlooked due to lack of awareness, tight deadlines or just laziness — as long as it works, the client can’t tell if a server is set up badly.

WordPress & CMS bloat

Popular CMS and e-commerce platforms such as WordPress, WooCommerce, SquareSpace, Magento and Shopify offer great tools for building websites and are used as the default option by many agencies, but they often run on enormous code bases that are slow to load and grow more sluggish over time due to 3rd party plugins, heavy themes and layers of upgrades.

It’s common to see developers install fully-featured plugins and themes to solve simple tasks, saving their own time at the cost of their end users’ frustration. Eventually this grows into a soul-sucking, tangled mess that becomes painful to work with, where modifying plugins feels like disabling a bomb that could bring the whole site down at any point.

It’s possible to optimise WordPress and even achieve 100 PageSpeed score, but it rarely works out that way. Developers have to spend extra time and budget fighting against the inbuilt mess rather than working with it.

More modern alternatives include Grav, Perch and Craft, though these options have fewer pre-made themes and plugins.

We sometimes build 100% bespoke content management systems using NodeJS, MongoDB/MySQL and Express, which are tailored for client needs and lightning fast. Our MSD Vehicles hire/sales website can finish loading in the browser in less than 200ms under normal conditions when deployed, even with a database of users and vehicles.

How to speed up your website

Now for the good stuff — we’ll run through the most common methods of increasing website performance and how developers can implement them. If you have any questions just reach out to us, we’ll talk your ears off about this topic all day.

If you want a thorough checklist for development, David Dias’ Front-End Checklist is a great place to start.

Start by running your website through Google PageSpeed Insights , which results in a detailed list of where your website could improve, along with tutorials and a useful .zip of your optimised images and CSS/JS assets.

Here’s the overview in rough order of priority, then we’ll break the topics down individually:

Configure your web server

- Cache static content

- Enable gzip compression

- HTTP/2 & SSL

- Use a CDN

Compress images

- Reduce file size

- Use responsive images

- Use compression plugins

Optimise CSS & JS

- Strip unnecessary code

- Scrap jQuery

- Async load JavaScript

Reduce HTTP requests

- Bundle & minify assets

- Lazy load content

- Use sprite sheets

- Watch your WordPress plugins

Prioritise visible content

- Inline critical CSS & JS

- Set above-the-fold dimensions in CSS

- Optimise the waterfall

Reduce time-to-first-byte

- Cache dynamic content

- Check server latency

- Try a static site generator

Configure your web server

Your web server is the perfect place to start optimising, because sometimes all it takes is a single line or block of code to make a huge difference.

Start by taking control of your hosting — we host in the cloud using Amazon Web Services, or DigitalOcean is a great alternative.

Sometimes clients will buy a domain name with shared hosting included, but these packages are limited in terms of speed, location and configuration. They also add extra management overhead when it comes to switching between projects.

We prefer using Nginx installed on a Ubuntu EC2 instance which hosts multiple websites, and we’ll use this setup for the following sections. This way we can control exactly where our server is, how powerful it needs to be, what software is installed, how it’s configured and what’s being hosted on it.

When you’ve made any changes to the config files, remember to use the following command to reload the config:

sudo service nginx restart

Cache static content

When a browser wants to download an external resource such as an image or script, it checks a local cache to see if it’s been downloaded recently.

You can control the exact amount of time that each file stays in the user’s browser cache before expiring by setting the Cache-Control HTTP header. If no header is set, the browser will re-download the file on every page, which slows performance unnecessarily. This header alone can greatly speed up a website.

Here’s how I set a maximum expiry date inside an Nginx server block:

location ~* \.(?:css|js|jpg|jpeg|gif|png|ico|cur|gz|svg|svgz|mp4|ogg|ogv|webm|htc|woff|woff2|ttf|otf)$ {

expires 1y;

access_log off;

add_header Cache-Control "public";

}

With this setup the browser will keep static files for a year before re-downloading them. You’ll need to cache files for at least a week before PageSpeed stops yelling about it.

Just be aware that if you update the files on your server, browsers that have already cached the file will keep using their outdated version. To force a reload, you can change the name of the URL or version it manually with a query string like so:

<script src=“/script.js?v=1.0”>

It’s also possible to add a file hash to the URL using Gulp for automatic versioning.

You can’t control the cache duration for files that you don’t host, such as scripts or fonts loaded from an official repository. It’s usually best to try and host them yourself, but some resources like Google Analytics need to be loaded from Google servers which set a 2 hour expiry time, knocking 1 point from your PageSpeed Insights score.

Enable gzip compression

gzip tells your server to compress text assets like HTML, CSS and JS before sending them across the network, reducing their size by up to 90%! There’s really no reason to have this disabled, and it’s included in all modern web servers.

Find your nginx.conf file and make sure this line isn’t commented out with a #:

gzip on;

Although not required, you can add gzip_min_length 256; on a new line to avoid compressing tiny files that don’t benefit from gzip. The rest of the gzip lines are fine staying commented out unless you want to change them.

HTTP/2 and SSL

Back in ye olde days of 2015, HTTP/1.1 was the protocol that all websites used to transfer files. It was released in 1999, and was quickly becoming a bottleneck for speed due to being designed for simpler times.

HTTP/2 brings a huge speed boost to the underlying protocol of the internet. It’s backwards compatible and easy to set up so it should be used by default for all new sites.

- Multiplexing — Many requests can be made at the same time over the same connection, previously only 6 files could be downloaded at once

- Single TCP connection — Just one persistent connection is needed to download all website resources, rather than a new one for every file

- File priority — The server can prioritise some requests above others

- Server push — The server can push files to the client without them requesting it, usually files that they’ll need later

- Header compression — Saves bandwidth rather than re-sending the same headers with every request

Here’s a basic HTTP/2 Nginx set up to go inside your server block. The only difference is the inclusion of http2 in each listen line.

listen 80 default_server;

listen [::]:80 default_server;

listen 443 ssl http2 default_server;

listen [::]:443 ssl http2 default_server;

// Certbot will take care of everything below this

ssl_certificate path_to_cert.pem

ssl_certificate_key path_to_key.pem;

// Redirect all HTTP traffic to HTTPS

if ($scheme != "https") {

return 301 https://$host$request_uri;

}

All HTTP/2 connections require SSL encryption to work, but with the rise of Let’s Encrypt you can do this for free in about 2 minutes. If you have SSH access to your server, Certbot will automagically detect the websites you’re hosting, generate and install your certificates, update your server config and renew your certificates every 90 days… we love automation 🤖

Certbot is super easy to install on Ubuntu via SSH:

sudo apt install certbot

sudo certbot

The certbot command will give you a list of any websites that it can detect on your server, ask you which ones you want to secure and whether you want to redirect all traffic to HTTPS (which you probably should). It’s as easy as that! If you run into problems, the official documentation covers manual setup.

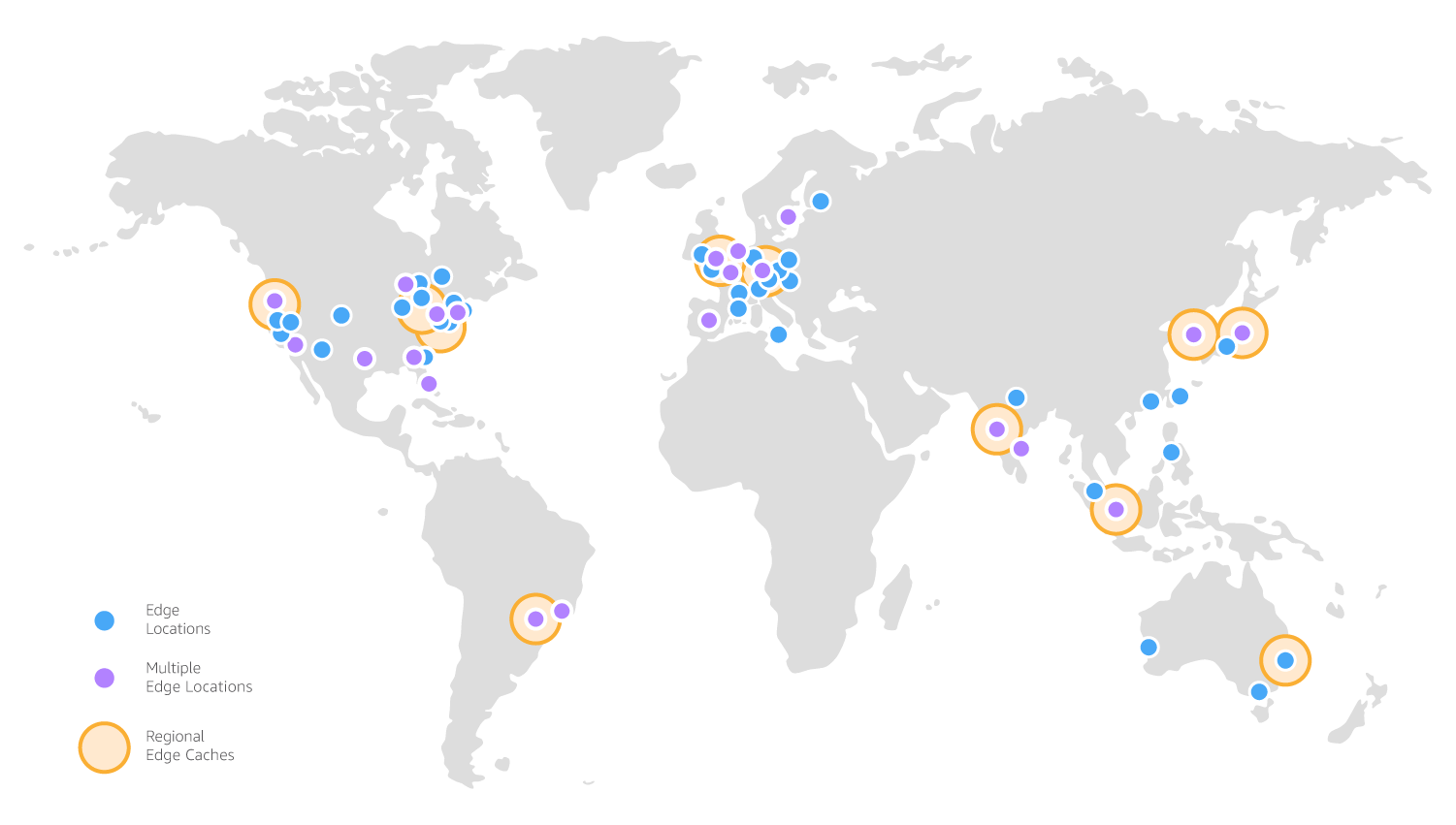

Use a CDN

A Content Delivery Network such as Cloudflare or CloudFront sits in front of your main web server (called the origin), distributing its content to dozens of cache locations around the world.

AWS CloudFront cache locations, 2018

When a user visits your website, they are routed to the nearest cache which serves your static files if it has them. If the files have expired or they’re not in the cache, they are fetched the origin server and forwarded on to the user. This is ideal if you have heavy traffic or visitors from around the world trying to access your content.

CDNs take a huge amount of load off your web server and can handle virtually unlimited traffic, so they’re perfect for serving up images, videos, scripts and other static content.

You can also cache dynamic HTML responses, even if it’s for 1 second, so that your server isn’t crushed by a flood of traffic.

A slight downside is that it can take up to half an hour to force a re-distribution of cached files that haven’t yet expired. We also tested CloudFront for our website and found that the page actually loaded ~100ms slower than when hosted directly on our Ubuntu server.

Compress images

Most websites have some level of image bloat, and in the worst cases multiple photos are uploaded straight out of the camera weighing 5-10MB or more. We’ve seen a gallery with 50 images serving full camera resolution images as the thumbnails for a 220MB total page size 🤦♂️

Reduce file size

Saving your images in the correct format at the exact size they will be displayed is crucial. Photoshop and Sketch have great tools for this, and setting the JPEG quality to 50 is usually enough.

Another option is to save your images at max quality with the correct dimensions, then run them through an online tool like TinyPNG or PageSpeed Insights.

- JPEG — photos and soft edges

- PNG — hard lines, text and solid colours, reduce the number of colours to the minimum without banding

- SVG — vector-based logos, illustrations and animations, use over PNG where possible

- MP4 — any video or animated content

- GIF — probably never due to massive file sizes, use PNG for stills and MP4 for animations

Use responsive images

Loading optimised versions of the same image for each screen size can be a big bandwidth saver. No need to load a 2000px banner image for a mobile site! It’s possible to shave seconds off your mobile load times with these methods.

The <picture> tag can set different image sources using CSS media queries. Old browsers will fall back to the nested <img> tag.

<picture>

<source srcset="mobile_banner.jpg" media="(max-width: 400px)">

<source srcset="small_banner.jpg" media="(max-width: 768px)">

<source srcset="med_banner.jpg" media="(max-width: 1024px)">

<source srcset="dektop_banner.jpg" media="(min-width: 1025px)">

<img srcset="dektop_banner.jpg" alt="Banner Image">

</picture>

You can use max-width, min-width, max-height, min-height, orientation and more in the media queries.

It’s also possible to do a simpler version inside a single <img> tag:

<img src="mobile_banner.jpg" srcset="small_banner.jpg 1.8x, med_banner.jpg 2.5x desktop_banner.jpg 3.5x" alt="Banner Image" width="400px" />

Image compression plugins

Uncompressed images usually appear on content-managed websites with no image optimisation plugins. The client shouldn’t be expected to know how to compress their images, so make sure the website takes care of it automatically.

Optimise CSS & JS

Large front-end frameworks such as Bootstrap, Foundation, jQuery, Angular and React are fine on their own and can lead to faster development times, however they’re often used as a crutch for simple tasks like drop-down menus or basic animations, and include huge amounts of unused code.

Strip unnecessary code

Do a full audit of the frameworks and libraries that you’re using, and strip out or rewrite functionality as necessary. It goes without saying that this is easier to do at the start of a project!

Try minimal libraries like Pure CSS and HyperApp, or write your code from scratch. If you’re using Bootstrap, customise it to reduce the file size!

Scrap jQuery

With the rise of CSS animations and ES6 JavaScript, we have powerful tools already built into browsers. If you’re pulling in 85KB of jQuery just to animate a dropdown, it’s probably time to upgrade your code!

jQuery is great for making AJAX requests easier, but if that’s all you need then axios is even smoother to use at 4.7KB gzipped and .fetch() is supported natively in all modern browsers except IE11.

// jQuery (ES5)

$.ajax({

url: "/data",

success: function(result) {

doSomething(result)

}

})

// axios (ES6)

axios.get('/data').then(result) => {

doSomething(result)

})

// fetch (ES6)

fetch('/data').then(result) => {

doSomething(result)

})

Websites like You Might Not Need jQuery and PlainJS are fantastic resources for replacing heavy libraries with small snippets of vanilla JavaScript code. If you need to boost your JS skills, Wes Bos has some phenomenal courses that we love and use.

Async load JavaScript

Most scripts aren’t necessary to render the initial page, but by default all <script> tags force the browser to pause rendering, download the external file and run it before continuing with the page.

Move non-critical <script> tags to the footer and add an async property to stop them blocking the page load. This allows the browser to move on with rendering whilst sending out the request asynchronously, and the script will be run whenever it gets back from the server.

Just bear in mind that with this approach you can’t guarantee the order or time in which your scripts will be run. We prefer inlining any small scripts, which we’ll get to later.

Reduce HTTP requests

Every external request your browser sends out takes extra time, and is affected by the latency between you and the server. On a 3G network latency can easily hit 200ms per request, so every request counts.

Bundle & minify assets

Gulp will supercharge your front-end workflow, and it’s hard to imagine life without it. Use it to minify and pre-process your JS & CSS, concatenate them into a single package, auto-inject changes into your browser without reloading (absolute godsend 🙏) and a whole lot more.

We recently wrote about using Gulp to easily generate responsive emails with MJML, and we’ll probably do a full modern front-end workflow post in the future.

It’s a whole topic in itself, but well worth digging into. Sitepoint’s Introduction to Gulp.js is a good place to start.

Lazy load images

If you have an image-heavy site, consider lazy loading them as they’re scrolled into view, otherwise they’ll be eating up the bandwidth during the initial page load that should be used for above-the-fold content. If you have a carousel banner, make sure that your code/plugin lazy loads the remaining images as they’re needed.

Generate a sprite sheet

If you have lots of small images or an icon set that requires multiple HTTP requests, consider packing them all into one sprite sheet. ZeroSprites is our weapon of choice here.

This generates a single PNG file with all of your icons included, which then gets cropped using the supplied CSS classes.

.sprites {

background: url(sprites.png) no-repeat;

}

.435264 {

width: 704px;

height: 371px;

background-position: 0 0;

}

.435264 {

width: 704px;

height: 371px;

background-position: 0 -372px;

}

/* ...More icon classes */

Watch your WordPress plugins

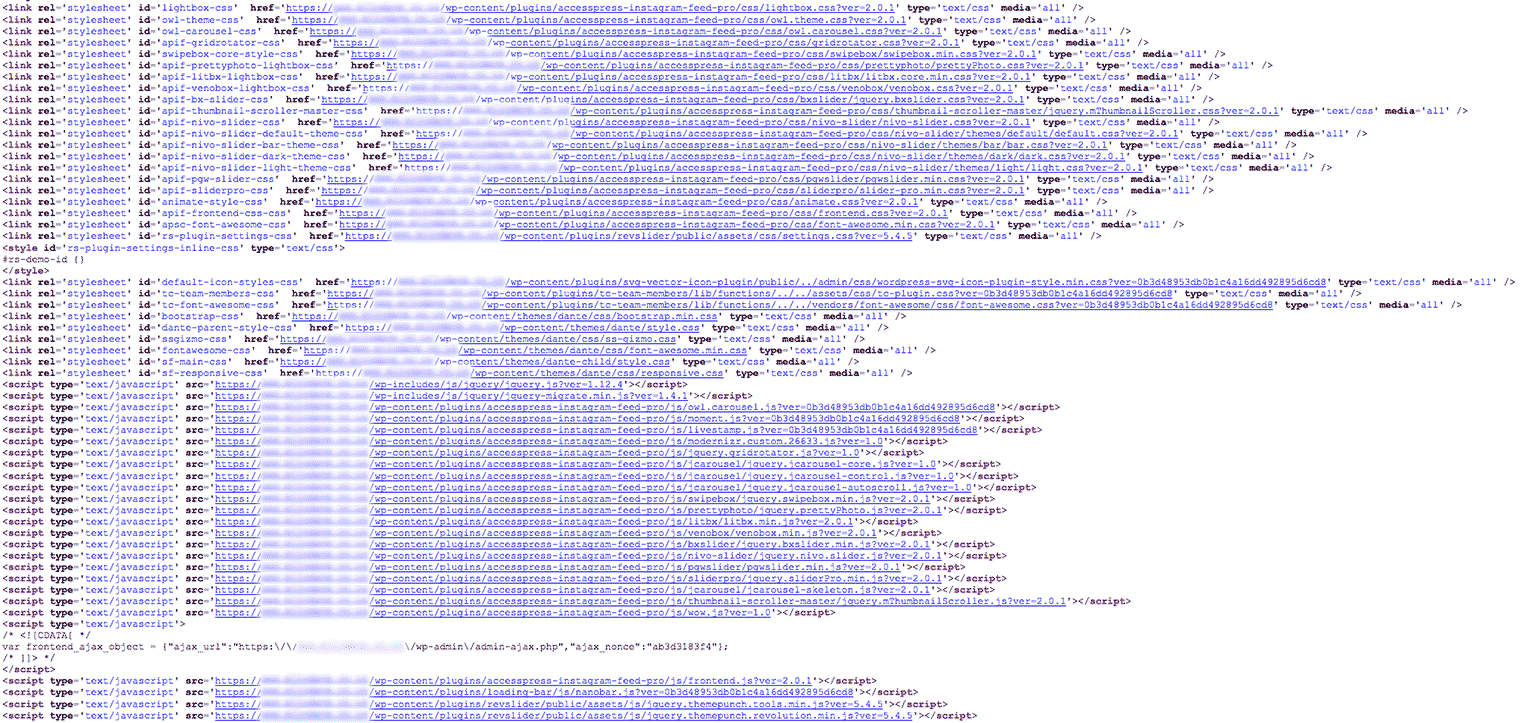

WordPress (noticing a theme here?) plugins are notorious for loading masses of extra code into the browser, and it’s hard to weed them back out without breaking things. We recently came across a brand new WordPress site for an agency that sells website development. Here’s just one portion of the <head> code:

In total, there are 53 Javascript and 33 CSS files which block the page and take a full 6 seconds to load on Virgin’s fastest 400Mbit broadband, and 44 seconds on 3G internet. The page has a 1.2 second TTFB, no gzip and no Cache-Control header so all of the assets are uncompressed and re-downloaded on every page! 😡😡😡

A staggering portion of these are coming from a single 3rd party Instagram feed plugin, yet the page has no Instagram content. 🤔

Audit your plugins!

Prioritise visible content

Pay close attention to the order in which your CSS, JS and images are loading, and try to minimise the time it takes for the browser to render above-the-fold content. Google have excellent advice for optimising the critical render path.

Inline critical CSS & JS

If your CSS weighs less than 100KB or so we recommend just inlining the minified version directly into the HTML using Gulp or your templating system of choice. This way the browser can instantly start laying out the page with the just first HTML response rather than waiting for an external file request to return, and the page feels much snappier as a result.

See The Guardian’s recently redesigned website for an example of inlining the main payload of CSS.

With this method you don’t get the benefit of having CSS cached in the browser because it’s re-downloaded on every page, but once gzipped 100KB of CSS turns into ~15KB and is transferred in an instant. We’re still seeing < 200ms load times with this approach. If you’re able to separate your above-the-fold CSS and just inline that part, go for it!

We also inline most of our small JavaScript files to reduce HTTP requests and increase the overall page speed.

Set above-the-fold dimensions in CSS

Everybody’s tried to click on something the instant after an advert or image pops in causing the page to re-arrange itself, and felt the internal rage that follows as you mash the back button too many times.

I spent hours trying to figure out why PageSpeed Insights was knocking my score down for Prioritise Visible Content, and this turned out to be the reason (and an important lesson).

If you have images above the fold, make sure the height attribute is clearly defined in your CSS. By default the browser will render the <img> element at 0 height until the image file loads, at which point it will calculate the width/height ratio and resize the element to fit, causing the page content to jump around.

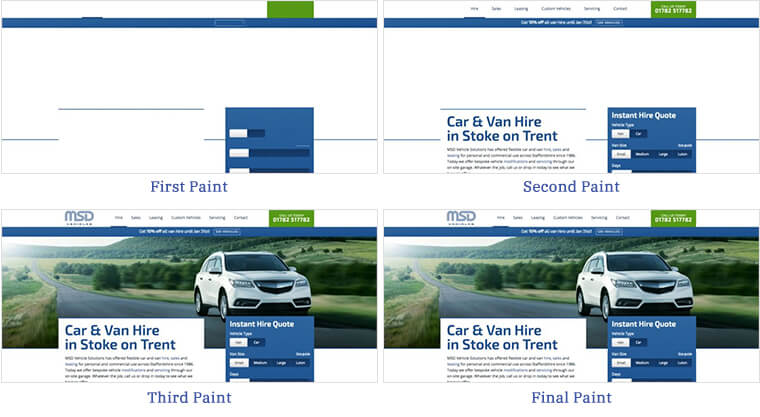

Notice on the MSD Vehicles website how even before the text and images have loaded, the page is laid out with exactly the right dimensions to accommodate them. This doesn’t strictly make the page load faster, but it feels faster once you’ve done it because the content blocks are visually in place sooner. The final paint happens in just 140ms because we’ve spent time optimising for visible content.

You can use the Network tab in Chrome’s developer tools to capture screenshots of each paint stage and analyse where content is jumping around, and try to fix the dimensions in CSS.

This also goes for advertising blocks. Especially for advertising blocks.

Optimise the waterfall

Most browser developer tools have a Network tab that shows a waterfall graph of all the HTTP requests made whilst the tab is set to record, along with details of the file sizes, number of requests and loading times for different stages. It’s extremely useful for analysing the order in which files are requested and spotting issues.

In the Network tab, you can turn off your browser cache to force all assets to re-download and artificially limit your network speed to simulate mobile devices on 3G and see how that affects the graph.

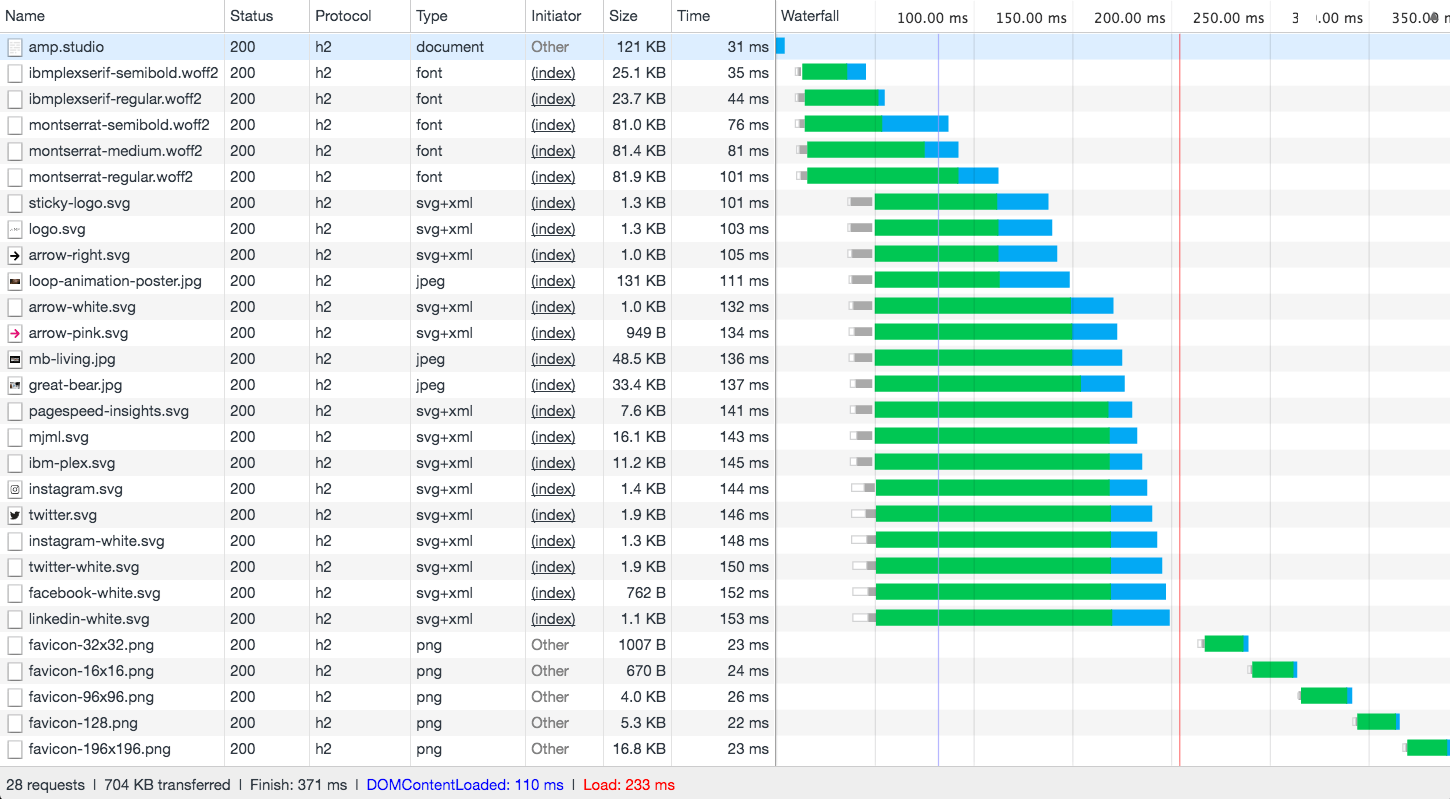

Here’s the AMP homepage waterfall in Chrome, without the video that streams in afterwards:

Most of the HTTP requests are made in bulk as early as possible because they’re included in the first HTML response, resulting in a 233ms load time for this particular page.

Inlining CSS allows the browser to request background images, icons and fonts immediately, rather than waiting for the external CSS to download, parse and request the files in a second round.

This is where HTTP/2 helps massively, allowing us to process hundreds of files in one go. When using HTTP/1.1 the requests get bottlenecked and staggered across time due to a limit of 6 requests.

The 4 font files at the top load in earlier than everything else because we’ve added preload links to the <head>, before the inlined CSS. This helps the text to render as early as possible in supported browsers. You can preload any files you like to get the requests sent off before the rest of the HTML or CSS is parsed.

<link rel="preload" href="/assets/fonts/ibmplexserif-semibold.woff2" as="font" type="font/woff2">

<link rel="preload" href="/assets/fonts/ibmplexserif-regular.woff2" as="font" type="font/woff2">

<link rel="preload" href="/assets/fonts/montserrat-semibold.woff2" as="font" type="font/woff2">

<link rel="preload" href="/assets/fonts/montserrat-regular.woff2" as="font" type="font/woff2">

I can’t quite work out why Chrome loads in all of the favicon sizes separately at the bottom of the graph, but it doesn’t seem to affect the loading time which is marked buy a vertical red line.

Reduce TTFB (time-to-first-byte)

TTFB measures the delay between your browser asking for a webpage and receiving the initial HTML response from the web server. A faster TTFB means that a visitor’s browser can parse the HTML and send out the requests for all of the external images and scripts earlier.

Cache dynamic content

In a CMS all of the page content is usually stored in a database, so this needs to be fetched, processed and dynamically placed into a template before serving the resulting HTML back to the user, increasing the TTFB.

The problem is that many websites serve exactly the same page to each user, but the server still has to render the page every single time! Each page can take half a second even on a fresh WordPress site with no plugins.

Using a plugin like WP Super Cache for WordPress helps to save the server from re-rendering the same content for every visitor, reducing the TTFB.

Check server latency

Make sure that your website is hosted in the same country that it’s being primarily accessed from to reduce the time spent waiting for a response. Our servers are in London, so we’re getting speedy ~20-30 millisecond responses to our Stoke-on-Trent office 150 miles away. There’s no set goal for ping, but lower is always better.

ping www.amp.studio

Using a CDN (discussed earlier) will help to reduce latency internationally.

Try a static site generator

For maximum performance, consider building a completely pre-rendered website from scratch with a static site generator such as Jekyll (like this website) or Hugo. This approach offers ultimate control and speed for developers, but lacks the ability for clients to control the content.

We’ve found that some clients rarely if ever update their websites even with access to a CMS, so in these cases we prefer building static websites. The client can ask the developer to update the website on the rare occasion that it needs doing, and it’s usually cheaper for the client overall because the initial build takes less time.

You can still have dynamically generated blog posts and project pages, they’re just rendered into HTML on your development computer instead of on the server every time the page is requested. For the Twitter feed on our otherwise static homepage, we pull the data in via AJAX from a custom API.

Our own website has a ~25ms TTFB when deployed because the pages are already rendered into static HTML files, so the web server can instantly respond without processing any PHP or backend logic.

Conclusion

Whew, that was a long one.

Hopefully this post encourages clients and developers alike to start taking speed seriously when it comes to increasing the revenue and SEO ranking of a website.

We’re barely scratching the surface and each topic could easily be a post on its own, so email us or reach out on Twitter with any questions or comments.